Towards an Indigenous History of West Virginia

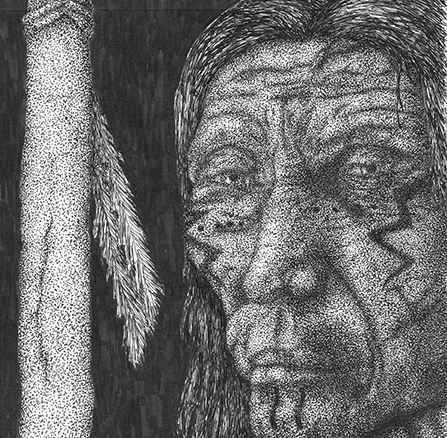

It surprised many of my West Virginian friends when I began my work on Native Americans in the state. They had a vague sense of there having been Indians at some great distant time, “I mean, they built the mounds right!?” The next mention was of Indian princesses jumping to their deaths and bloodthirsty warriors indiscriminatingly killing white settlers in the 1760s. But after the Revolution, most people believe that Indians had disappeared completely. Others, I spoke to, recited the more pervasive myth that Indians didn’t live in the state as “it was just a common hunting ground!” This is straight out of every eight grade West Virginia studies textbook. The current draft still speaks of Indian Princesses even if they have three pages about the Moundbuilders and a single page about the French and Indian war. I knew that there was so much more there.

Here is the briefest history of indigenous people of the state. We have evidence of people occupying the state as early as 15,000 years ago at the tail end of the last Ice Age. Though evidence is focused in the northern half of the state, the earliest people hunted the large mammals and collected a wide range of foods like herbs, berries and bark. As the Earth came out of the Ice Age, large mammals died off and the people adapted to the new climate which provided a more diverse food supply. Progressive these people developed a collection of plants that they began to select and cultivate. This led to the developed into full-blown agriculture very quickly and from it a new cultural pattern developed and spread across the region, the Adena culture pattern. Their mound building and large-scale religious practices lasted for over a millennium and was carried on by the Hopewell.

3,000 years ago, corns, beans and squash were introduced leading to development of more settled villages and complex societies. Unlike many societies nearby, the peoples living along the rivers in the southern half of the state did not become stratified. Nearly two thousand years of growth and expansion followed. Indigenous peoples became more diverse and settled in the Appalachian Mountains farming and foraging within more entrenched territories. We are not certain what languages were spoken in West Virginia during the protohistoric period, but dialects of Algonquian, Eastern Siouan and Iroquoian were known to be present when Europeans arrived. The peoples mentioned in the story speak Tutelo (Yesanechi). Villages seem to have been multi-ethnic and diverse autonomous political units so multiple languages coexisted in the same space. Tribes as we know them in the eighteenth century had not yet formed.

After the visits from Lederer in 1670, Batts and Fallam in 1671, and Needham and Arthur in 1673-1674, the Appalachian Mountains were soon abandoned by many of the Siouan speaking peoples. They left to join other more numerous peoples after the effects of Indian warfare, slavery, disease, social chaos and climatic changes. By the turn of the eighteenth century, most of the state had been cleared though a few small pockets remained. As Siouan control dissipated and the management of the mountain valley ecology stopped, the gardens and forest grocery stores became overgrown and lush.

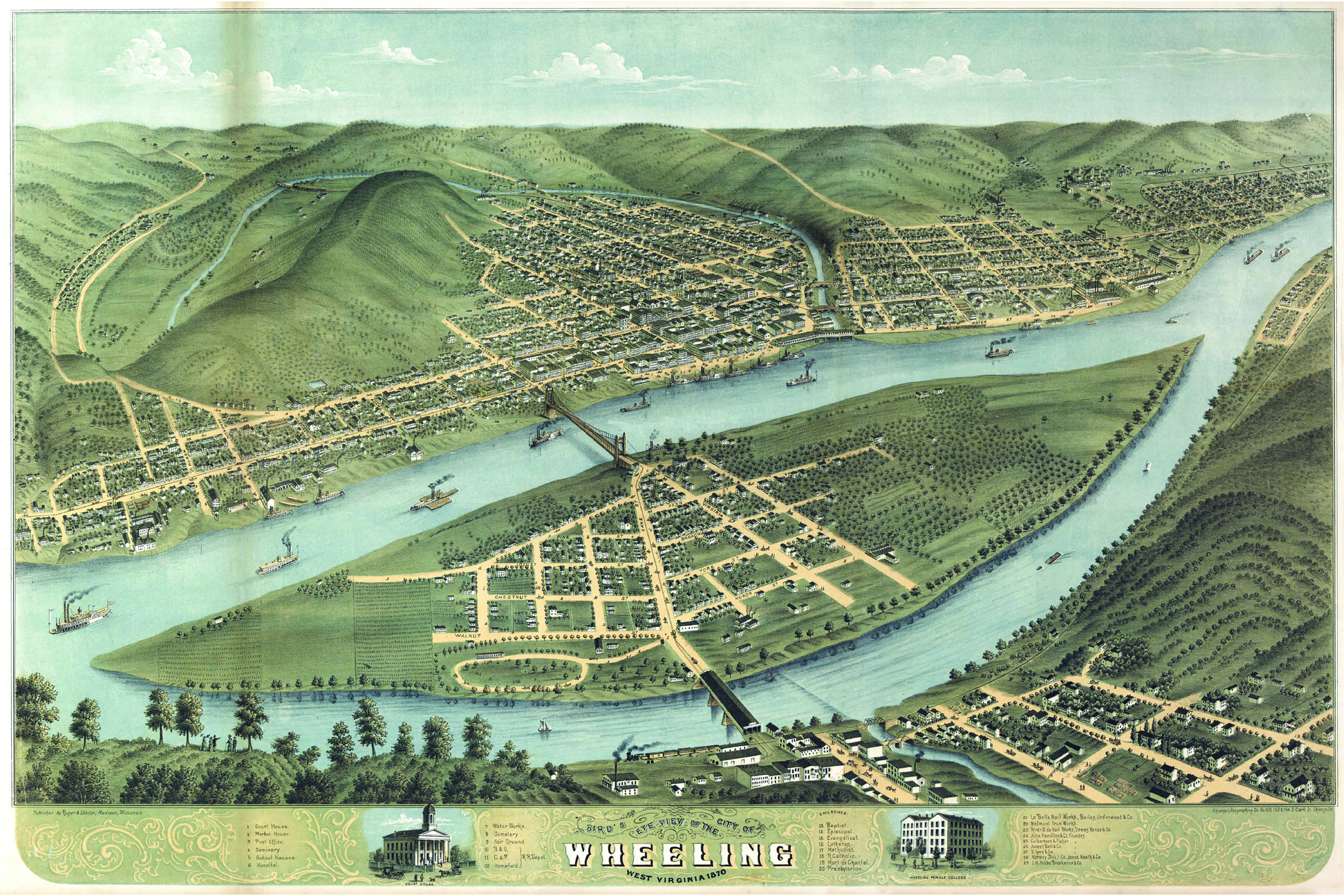

It was not long before the Shawnee and Iroquois became interested in the well-feed and healthy deer of the Appalachian Mountains and began to settle in the region. This interest attracted the attention of the French and English as well. Their conflict over lands only recently occupied by other Indians became the spark that lit the world on fire in the global conflict we call the French and Indian War, also know as the Seven Years’ War. The Algonquian and Iroquois speaking peoples calling the state home understandably claimed the right of conquest as proof of legitimate ownership, and argument that the English would inevitably coopt. Shawnee and Iroquois were able to maintain a semblance of control for another decade. The beginning of the end of recognized occupation was sealed in a small but deadly attack by the Virginia militia in 1774.

After this point, most Native people left the region, but those who stayed tried to pass as white if possible or where labeled mulatto and treated like slaves and second-class laborers. Research is suggesting that more Indians stayed in their homeland, but their story is still being uncovered. Any chance for Native people to live openly was destroyed with the tight ratification of the Indian Removal Act of 1830. Till the passage of Civil Rights legislation in the 1960s, Native people lived in fear of being labeled or targeted.

Today, there are almost four thousand Native people and another nine thousand who identify as multiple races including Native American. For these people, and the diverse ancestors of former residents, this story will hopefully begin to shift the conversation. Instead of the traditional narrative of common hunting grounds, we should focus on the effects of indigenous people and their decisions in the course of their own history. Native Americans have been in the state long before it existed, are still here, and will always be present in the state. We have a duty to include and amplify indigenous voices when telling the story of the state.