Why bother with Colonial period history?

Huge black hats with belt buckles and thick woolen black coats, pants and dresses or red jackets, wigs and tri-corner hats, quill pens and muskets; these seem to be the main memory my students had when asked about the colonial period. This would be accompanied by sleepy stares of boredom or even eye-rolls. The colonial period is my favorite period to examine in North America and remains informative when looking at the reasons behind most of the best and worst elements of modern society. While many of my US students feel that it was an unimaginably long time ago, but in the scheme of even European history, much less the history of indigenous people in North America, the colonial period is still very recent and more importantly it is still the foundation of our current social, political and economic landscape.

As a child, I always found the teaching of the colonial period painfully dull and uninformative, I could not see the reasons for their actions, epically when it came to race, class, and gender. But as I matured and began grad school, I realized that modern history classes neuter the colonial period by not portraying the complexities of real living. There were huge holes in the narratives presented in textbooks where entire communities and races should have been but were avoided to present a uncomplicated straight-line manifest destiny narrative. I could see it then, but once the realization dawned, I found myself feeling impelled to shine light on those areas of the story. If colonial history has fallen out of favor, it may be because people accept the holes and narrative and then stumble into the present blinkered by their unwitting ignorance. This alone is something that has real world consequences.

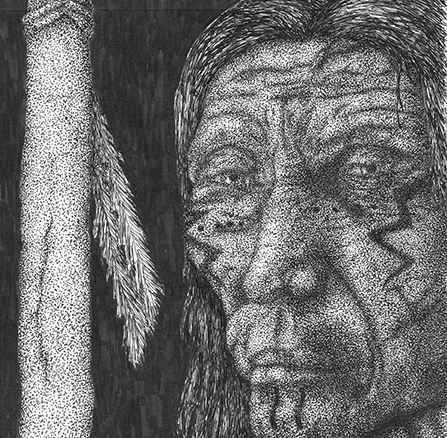

The colonial period, roughly 1440-1770, set the stage for race relations that haunt the US into the present. Slavery did not begin during this period but became a permanent legalized institution in North America almost from the beginning of European settlement. This institution remains poorly understood amongst my students and many adults. Slavery was perpetrated against not just Africans but also Native peoples in North and South America. The social and government structures quickly incorporated slavery and race-based segregation right beside the rigid gender and class norms transplanted from European. But the people Europeans viewed as lesser fought the oppression in surprising ways that have been ignored and hidden in many history classrooms. As the protests for civil rights of minority communities continue, I have so many assume that the fight began in the 1960s, its never ended for over 400 years.

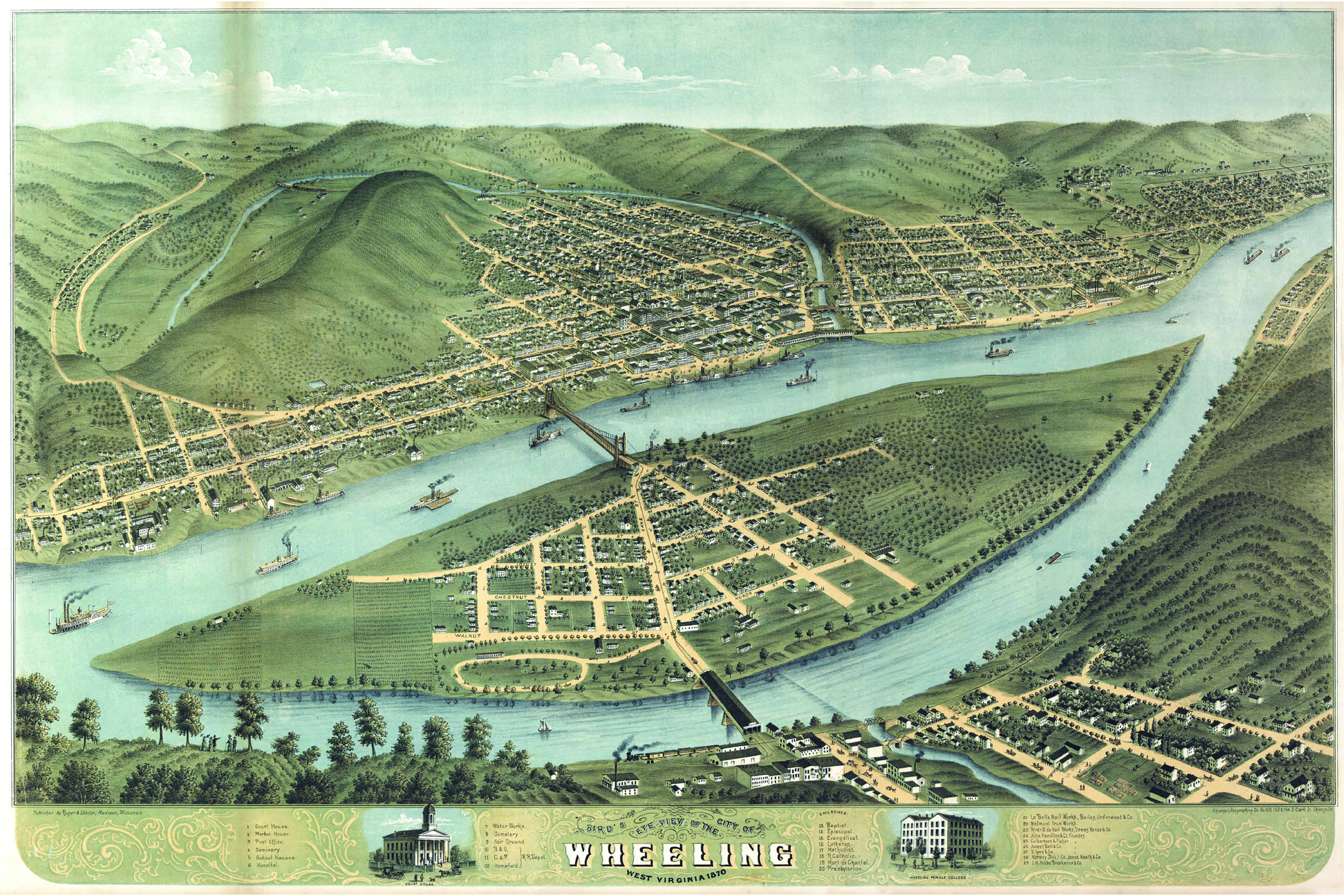

The colonial period can be viewed through the lenses of cultural terrorism, epidemiological nightmares, environmental chaos, geopolitical violence, or the expanding and changing economy. These situations have deep roots and must be addressed with this knowledge or any efforts will miss the tenacious roots that regrow any injustice in time. Colonial history teaches us to examine the effects of power structures and their inherent inequalities. Slavery destabilized white society leading to poor farmers getting pushed off their original tidewater land allotments and further west setting them at odds with indigenous peoples. Big business slave owners consolidated millions of acres from those small farmers and cut the out of the markets. For indigenous peoples, the options they had were complex and nuanced and often involved sacrificing tradition for maintaining access to their land, and heritage.

Colonial history teaches moments of cross-cultural collaboration and survival despite desperate odds, but this was in the context of a wide array of reactions from indigenous peoples to the European social pressures. It provides a relatively blank canvas to reform students understanding of the country. Collaboration was coupled with violence, coercion was bound to mutual benefit, and the scales of power swung back and forth for indigenous people until European people surrounded them during the eighteenth century. There are times when I find myself asking the very same questions the authors of colonial documents.